To build your own Itinerary, click  to add an item to your Itinerary basket.

to add an item to your Itinerary basket.

Already saved an Itinerary?

You are here: Arven vår > The Dream Poem

And it was Olav Åsteson

who slept a sleep so long…

On the thirteenth day of Christmas, January the sixth, in Catholic times known as Epiphany, a young man called Olav Åsteson awakes from a deep sleep which has lasted for 13 days. He dresses in his finest attire and rides to the church where he interrupts the service and regales the congregation with an account of his dreams. He recounts how he has travelled over the Gjallar Bridge to the very underworld, and that he has seen Purgatory and Paradise too, and even witnessed the very battle of Doomsday between the Devil himself and Archangel Michael.

This is the content of the visionary Norwegian ballad Draumkvedet – The Dream Poem.

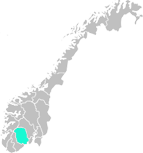

The poem is one of Norway’s most unique contributions to European music, literature and cultural history. The ballad existed in the oral tradition for several hundred years and probably survived up to recent times only because it was regularly sung in an isolated and geographically delimited area, deep in the mountains of south western Norway.

The riddle of The Dream Poem

Both Christian and pre-Christian elements are easily traceable in the ballad and yet the age of The Dream Poem remains something of a mystery. Suggestions as to its date of origin range from 400 AD to the 1700’s. Most probably the ballad originated sometime around the Black Death, around the 1200 to 1400’s, when troubadour ballads of this kind were popular amongst the aristocracy and were known amongst the general population too, included the peoples of Scandinavia.

The Dream Poem can be regarded as a local folksong from upper Telemark, even though we cannot be absolutely sure of its precise origin. However, it stands as part of a tradition of visionary poems from Europe, too. It has thematic similarities to both “Tundal’s Vision” (Ireland/Germany, ca. 1149, in Old Norse «Duggáls Leizla») and “Solarljod” (Iceland, 1200’s) as well as Dante Alighieri’s famous “The Divine Comedy” (Italy pre 1321).

The similarities to European visionary poems suggest that the author – if there is one – was a learned man, a priest, perhaps, or a monk, an aristocrat or a well-travelled businessman. It is also possible to consider that a Norwegian farmer’s son who had done some travelling could be involved. Whatever the case may be, we are familiar with various text versions, influenced by local singers and changed and adapted to suit local needs over the centuries.

A local folksong?

The ballad of Olav Åsteson was discovered in the mid 1800’s in west Telemark, Norway. It was the well-known folklore enthusiasts Olea Crøger, M.B. Landstad, Ivar Aasen, Sophus Bugge, Moltke Moe and Rikard Berge who wrote down a variety of versions of the ballad between the years of 1840 and 1910.

Their sources were for the most part women – older tenant’s wives as well as younger farm maids who were able to remember, to a greater or lesser extent, parts of a ballad that the folk of upper Telemark had sung over many generations and which was said to originally have had over a hundred verses.

The various versions we know of, are found over a quite limited geographic area and within a time frame of 60 years, from Maren Ramskeid of Brunkeberg in Kviteseid (ca. 1840), via Anne Lillegård from Eidsborg (1847) and Torbjørg Ripilen from Mo (1890) – both in present day Tokke kommune – to Marit Tveiten from Grungedal in Vinje (1910).

These and most of the other singers of the ballad lived within a radius of 30 km of Eidsborg Stave Church and since no other versions are found from other parts of the country, it can be assumed that in the 1800’s The Dream Poem was only sung in this district. However, it was probably sung a lot, including at funerals. It was said that everyone could sing at least a little of the ballad, but nobody could sing all of it.

Interpretations and Theories

In most of the well-known versions of The Dream Poem the protagonist is known as Olav Åknison or Åknesi. The name “Åsteson” is – like other reconstructions – a later rewriting. One thought that Olav might be the same as Norwegian king Olav the Holy (ca. 993-1030), who had a mother called Åsta. However, this is illogical as the tradition was to take the father’s first name and Olav would therefore be named Haraldsson. Even though there is little support for this theory today, the name Åsteson is the one that has stuck. Landstad for his part believed that Olav was identical with a Danish missionary called Ansgarius (in Norwegian Aasgaardsson).

In the same rather fanciful fashion, we have the “reconstructed” version of The Dream Poem by Moltke Moe (1894). This version was used over a considerable time period in school textbooks and was a blending of several different versions of the ballad, together with some “foreign” elements as old-fashioned lyric stanzas. His version, comprising more than 50 verses, reflects more the romantic need for a Christian national poem in the runup to Norway’s independence from Sweden (1905), than a reconstruction based upon thorough research.

The depictions in The Dream Poem have prompted many interpretations and theories. The agonising journey over the Bridge of Gjallar (a name possibly derived from the “Gelde Bridge”, referred to in a Danish ecclesiastical text from the 1400’s) is a classic journey to the Underworld as found in many mythological texts. However, could it also be possible that the references are to actual landscape features in upper Telemark with place names which we no longer remember, f. ex. “Heklemo” , “Våsemyrane” or "Broksvalin"?

The Dream Poem also came to the attention of foreigners. The Austrian philosopher and father of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner, became acquainted with it during a journey he made to Norway in 1910. He immediately translated the text into German and interpreted it as a text composed by a monk belonging to a religious “mystery school” during the 400’s in southern Norway. This is an exciting theory lacking supporting proof, even if there is some evidence that there might have been a Christian monastic order on the Norwegian coast in the 5th century.

Another speculative viewpoint – supported by priest and mystic Ivar Mortensson-Egnund, together with others – postulates that Draumkvedet is a metaphysical journey to the heavens, via the orbit of the sun, through the zodiacs and on to the Milky Way. Mortensson-Egnund was a priest in Fyresdal in west Telemark from 1910 to 1914, a time when interest in the Dream Poem was at its height. He also published own poems called “Draumkvæe» (1895) and interpreted The Dream Poem using his own archaic Norwegian language (1905).

At the opposite end of the scale we find Georg Johannessen, literary and cultural critic from Bergen. He suggests in a book of essays (1993) that The Dream Poem must be an imitation of a medieval poem, a falsification, written by Catholic activists after the Reformation as a way of criticising or irritating the Protestant Church.

The most serious researchers into The Dream Poem have been the Norwegians, Brynjulf Alver and Olav Bø, Swedish Bengt R. Jonsson and Michael Barnes from England. They are less speculative and discuss various alternatives and ideas, but nevertheless each concludes with his own individual theory. The only thing we know for sure is that we don’t know.

The Black Death and The Dream Poem

One of the lines in the ballad, “In Broksvalin there Judgment Day shall be” has been and still is subject to many interpretations. “Broksvalin” could be a room in the heavens – comparable to Valhall in Old Norse religion. However, it could also be a direct reference to the porch-like gallery built around many of the Norwegian stave churches (“svalgang” in Norwegian). Perhaps it even refers to the svalgang around Eidsborg stave church? Of course, we cannot know.

In 2024, Norwegian cultural researcher Herleik Baklid launched a theory that places "Broksvalin" at a farm in Fyresdal, called Brokke. A stave church ("svalinne") on that farm, probably built in the 14th century, was torn down in the 1600's and substituted by a timber church which was removed in 1846. The spot can be visited along the road RV355, a mile north of Fyresdal centre.

We can be sure that in the years following the Black Death of 1349 there was a growing need for religious practise outside the abandoned churches. Most of the priests had died, as had two thirds of the population. It takes no great leap of the imagination to think that the survivors of the plague soon created their own religious rituals for use at home and that they were based upon their own experiences of death and disaster.

Perhaps the Dream Poem was to play a central role in these times? Maybe a wandering traveller told the survivors about the religious visionaries that were to be found in Europe? And could this have been linked together with some of the ballads known in the region at that time? Perhaps the story of Olav was even based on real events – did a young man miraculously survive the plague after having been given up for dead? Was it a ballad that folk sang as a comfort in unusually difficult times?

Where The Dream Poem originated and in what ways it was used we may never know for sure. But there is no doubting the power of the visions and events presented here in song. The fact that the ballad has survived for so long is testimony to its discerning evocation of essential experiences and deep emotions – for both singers and audience.

Live song and Inspiration

The Dream Poem has inspired many artists since when it first became known, not least composers. Ludvig Mathias Lindeman was the first to publish music based upon The Dream Poem in 1853 (for voice and piano), 1863 (for polyphonic song) and in 1885 (for mixed choir, premiered in 1934). Throughout the 1900’s new works appeared in rapid succession: from David Monrad Johansen, Klaus Egge, Sparre Olsen, Johan Kvandal, Eivind Groven and Ludvig Nielsen to Arne Nordheim. One more recent production of The Dream Poem was in 2015 by the progrock band, Neograss.

There are many “original recordings” of the ballad to be found. For example those of Knut Askje (Lårdal, 1950’s), Tora Raknes (Kviteseid, 1950’s), Aslak Høgetveit (Vinje, 1966) and Endre Sandland (Kviteseid, 2000-talet). However, it is doubtful as to whether these recordings reflect how the ballad originally sounded as these versions are influenced by the written texts and melodies which L. M. Lindeman and the popular singer Torvald Lammers presented at the end of the 1800’s.

Many people are familiar with the LP recording made by Agnes Buen Garnås in 1984, where she sings another “reconstructed” version created by M. B. Landstad in 1853 based on Maren Ramskeid. Sondre Bratland (2002) and Berit Opheim Versto (2008) have also given out their versions. The Dream Poem is still presented in many places by local artists – often around the 13th Day of Christmas, January 6th.

Other artists have also been influenced by The Dream Poem: Aslak K. Svalastoga, Gerhard Munthe, H.G. Sørensen, Sveinung Svalastoga, Torvald Moseid, Anne-Lise Knoff, Ragna Breivik, Karl Erik Harr (exhibited at Grimdalstunet in Skafså), Borgny Svalastog, together with others. Small sections of Torvald Moseid’s 55 m long Draumkvedet-rug (1993) are part of the new Dream Poem exhibition at Vest-Telemark Museum in Eidsborg.

New Exhibition and Sound Art Installation

From the year of 2020 you can experience a special exhibition about The Dream Poem at West Telemark Museum, next to the Eidsborg stave church between Høydalsmo and Dalen, Upper Telemark. Part of the exhibition is a sound installation by composer and sound artist Natasha Barrett. It is based on to new recordings of The Dream Poem (accordring to Maren Ramskeid) by Ellen B. Nordstoga and Halvor Håkanes, made in the Eidsborg stave church.

For more information and opening times of Vest-Telemark Museum Eidsborg click here.

Listen to some short excerpts made from the sound installation:

Text: Tilman Hartenstein